Major and Minor Scales

Building on what we’ve discussed with the chromatic scale and interval posts, we’ll take a deep dive into the scales that we’ll use to practice guitar, solo, and analyze songs. Understanding these will help you immensely when you turn to the guitar magazines, start having conversations with other musicians, start playing with other musicians, or start to look to other songs to find out how they are put together. More than many other topics in music theory, scales and keys give you a shorthand to communicate and understand what’s going on.

Similar to the way that intervals can be broken down into melodic and harmonic intervals, keys and scales have a similar relationship. Scales in the most basic definition organize a specific pattern of notes from the chromatic scale. These specific groups of notes allow us to create harmonic structures and patterns for us to play around with. It then lets us express ourselves melodically within the context of the harmonic environment we’ve created. These come together to let the audience recognize a “happy song” or a “sad song.”

Major Scales

Here we’ll focus on major and natural minor scales so we can understand the context for keys. Then later on we’ll circle back to the other scale types you’ll come across.

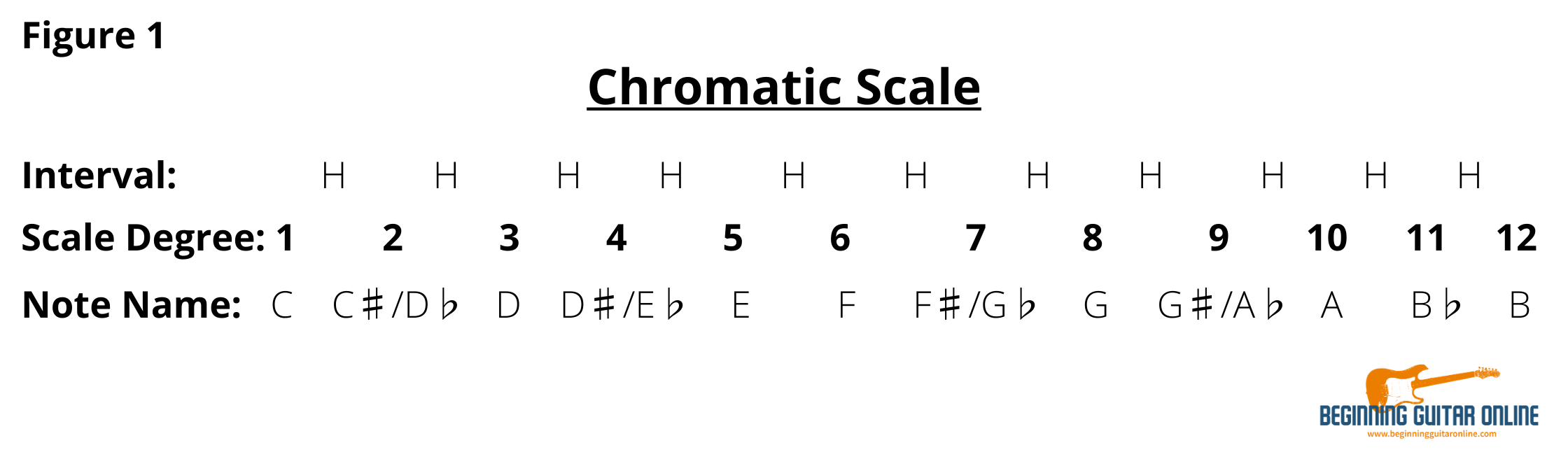

Bringing back Figure 1, above, as a reference since the major and minor scales come from specific groupings of seven of the notes you see above. Pick a note from above to start on (example: C) then use the following pattern of half and whole steps remembering that a half step is one fret and a whole step is two fret increments:

Whole - half - whole - whole - half - whole - whole

This is the pattern of intervals for the major scale. If you started on C then the resulting grouping of notes is the C Major scale depicted below in Figure 2.

If you were to start on any of the other notes in the chromatic scale and follow the same pattern you could put together the other eleven major scales. The seven notes in the major scales we’ll use to create the major keys, as well as build the various triads and chords within the keys.

Natural Minor Scales

We can do a similar exercise as above to put together the minor scales using a slightly different formula:

Whole - whole - whole - half - whole - whole - half

If you were to start on the note A you’d come out with the A minor scale depicted below in Figure 3.

Notice that the A minor scale above, along with the C Major scale we used as an example, don’t have any sharps or flats. The fact that these scales share the same notes, but start on different root notes make them relative scales. Typically, you’d only refer to the relative minor as most things in western music theory relate back to the major keys or major scales.

What this means in everyday guitar playing is that you can play an A minor scale pattern over the chords in the C Major key without sounding out of key. This is important when you’re starting out since you may only know one or two scale patterns before you start playing with other people.

Now if you look at the scale degrees of Figure 3 you’ll notice the ♭3, ♭6, and ♭7. This is the second method of discovering what notes are part of a minor scale. If you take any major scale (Figure 4) and you flat, or lower by a half step, the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees you’ll come up with the natural minor scale that shares the same root note. Figure 3 is reposted for comparison below.

This concept of raising or lowering specific scale degrees is an important one to grasp especially as we get into building complex chords or start working with modes.

A final thought before we jump into the keys and other scales, in your everyday music discussions certain terms may be omitted because they are implied. For example, instead of saying C Major when asked what key you’re playing in you’d typically respond by just saying “C.” This is also true with the natural minor scales. You’d typically just say “A minor” because the natural is implied. If you’re referencing a different type of minor scale you’d call that out specifically because those scales are used so much less frequently.

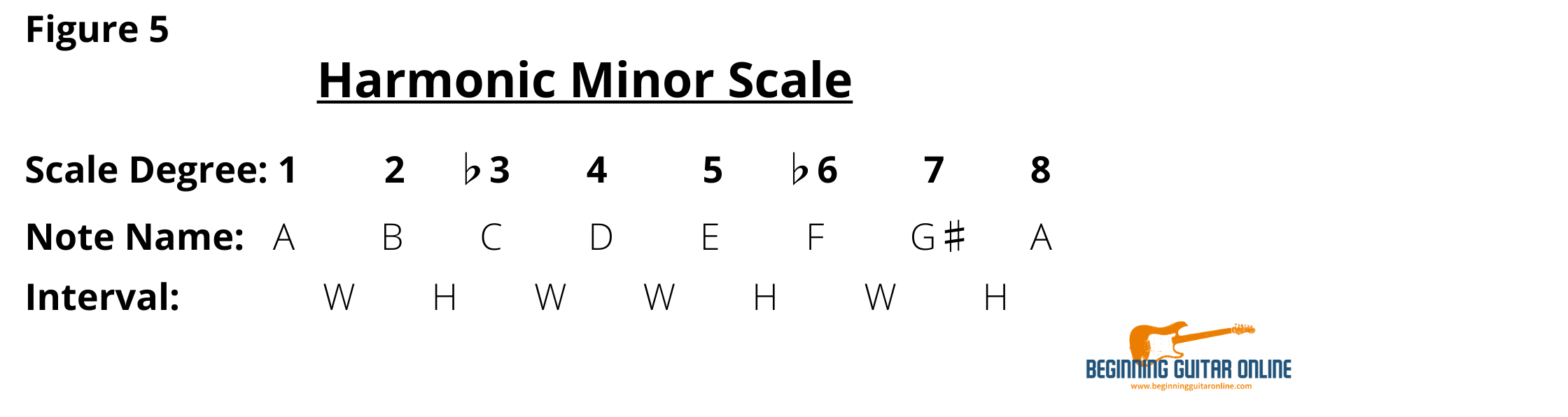

Harmonic Minor

The harmonic minor scale is a very important scale because of its historic significance. Early western music theory is heavily connected with the Catholic Church of Medieval and Renaissance Europe. As such the church mandated specific rules that impacted composers all the way through J.S. Bach’s time about how certain chords had to progress or how specific intervals were to be avoided.

One of the things that were mandated was how chord progressions resolved in perfect, or near-perfect, cadences. Without going into too much detail here, without the harmonic minor you couldn’t have a Major 5 chord so you could keep your job as a composer, or worse.

In more modern times, you’ll immediately recognize the harmonic minor scale from any of the movies of the last 30 years that take place in the Middle East, or fantasy shows like Game of Thrones when the “otherworldly” feeling is meant to be conveyed.

The unique things to call out in Figure 5, above, is that only the third and sixth scale degrees are lowered. This leaves a step and a half (or three frets) between the sixth and seventh scale degrees. The harmonic minor really stands out when it’s used on top of the related minor key.

Melodic Minor

The melodic minor as you see in Figure 6 is unique as it is played differently when you go up than when you go down the scale. As you go up the scale you’ll only lower the third scale degree to make it a minor scale but you’ll leave the major sixth and seventh scale degrees. After you reach the octave and you begin to descend the scale you’ll switch to playing a natural minor scale pattern with a flat third, flat sixth, and flat seventh.

As crazy as the scale formula seems, the melodic minor has a very particular sound that will be immediately familiar to you when you’re listening to jazz or classical music.

Summary of What We’ve Covered

I know we’ve covered a lot in this one, so don’t be afraid to come back to it as needed until the concepts sink in.

Major scales and natural minor scales are specific groupings of seven notes from the twelve you find in the chromatic scale

These groupings follow specific interval formulas

Major scales: whole - half - whole - whole - half - whole - whole

Minor scales: whole - whole - whole - half - whole - whole - half

Major and minor scales that share the same notes are referred to as relative scales

Natural minor scales are made up of a flat three, a flat six, and a flat seventh.

Another way to discover the notes in a minor scale or key is to take a major scale and lower (or flat) the third, sixth, and seventh scale degrees

Harmonic minor scales are central to chordal theory

Harmonic minor scales are made up of a flat three, flat six, and a major seventh

Melodic minor scales are played differently ascending the scale than when descending the scale. It’s played with a flat three, major sixth, and a major seventh ascending, then as a natural minor scale on the way down with a flat three, flat six, and flat seven