Chromatic Scale

All western music you’re familiar with, rock, classical, jazz, folk, blues, etc., is based on only twelve notes. Every scale, every key, every harmony, every chord that’s used in the styles above, no matter how complex it sounds, is some combination of the twelve pitches.

These twelve are the foundation of everything. Since they are so important, we are going to do a deep dive into the basics of the chromatic scale, so later we can explore what intervals are and how these are put together to build the scales and keys you’ll use to build chords and melodies.

Even if you don’t go really deep into music theory after this lesson, make sure you understand the basics really well because everything else you do when you sit and play will relate back to what we discuss here.

The Chromatic Scale

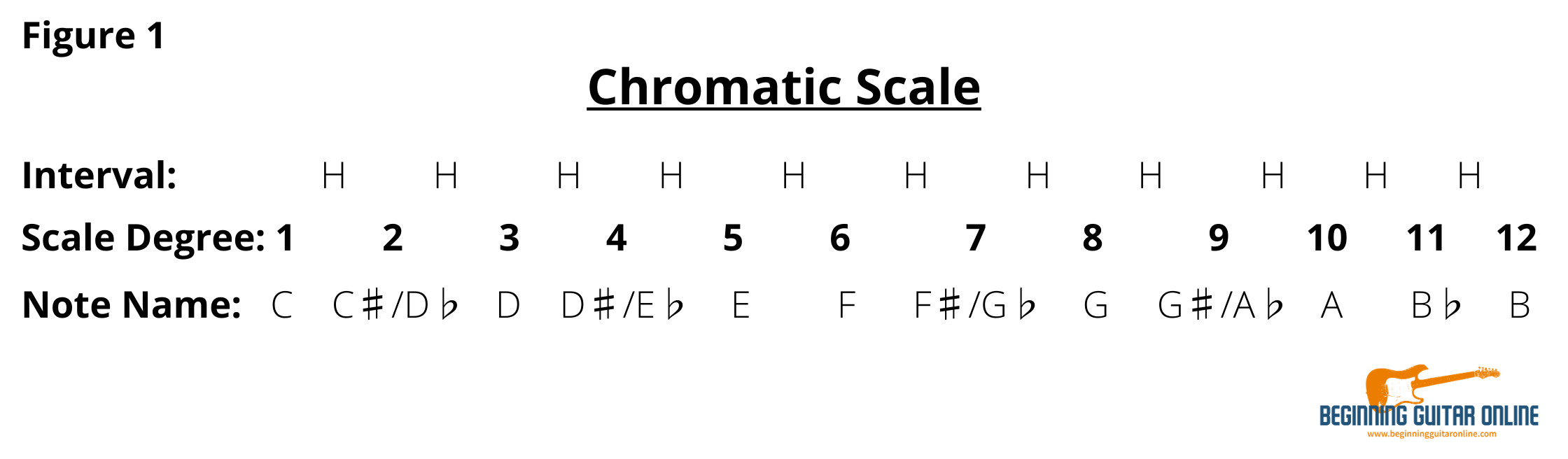

The chromatic scale is the only scale that uses all twelve of the notes and is the only scale in western music to move up and down in half step, or one fret, increments. Below in Figure 1, you see a depiction of the chromatic scale as well as three main things: 1) The numeric scale degrees, 2) the pitch, or note, names, and 3) the intervals between the scale degrees. Before we get too far down the rabbit hole, take a listen to Example 1, where you can hear how the chromatic scale sounds on the guitar.

In the figure above you can see the twelve scale degrees, the note names associated with each of the twelve scale degrees, and the half-step intervals between then. Where there is a slash between the note names this shows that these notes are the same even though one uses a sharp and the other uses a flat.

An example of one octave of the Chromatic Scale moving up and down the 5th string (A) beginning on the C found at the 3rd fret.

Scale Degrees and Pitch Names

Scale degrees in the context of the chromatic scale are fairly simple, but when we begin discussing the other scales and chord progressions, the scale numbers become a shorthand to describe what you should be playing. Especially with chords.

Now in the pure music theory realm, scale degrees have specific names to them (Figure 2). I would skip over this a bit since a lot of it isn’t necessarily used with the guitar, but we will make a lot of references to the tonic, dominant, and octave throughout our lesson examples.

For the pitch names, western music theory uses the letters A through G to represent the various notes on a guitar, or keys on a piano, that are played for a scale or chord. Now because there are seven letters from A to G, but we need to represent the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, we use accidentals.

Accidentals are symbols used in music notation to show a stepwise movement from a note. If you look back at Figure 1, you’ll see two accidentals, the sharp (♯) and the flat (♭), on either side of most of the “normal notes.” The third accidental is the natural (♮) but is often not shown as it is implied. So in most cases, if you see a “naked” letter, it is read as “A natural” or as just “A” with the understanding that the natural is implied.

Some note names show different things but are the same pitch, like A♭ and G♯. When you would use one over the depiction over the other totally depends on the context of the song and what you mean to show. This will make sense when we discuss keys and complex chords.

Sharps and flats represent a half step, or one fret, progression. This is what you heard when you listened to Example 1. Accidentals and their implications on how you play will be very important when we look at keys, advanced chords, modes, and scales used in particular staples like the Blues scale.

Now it bears worth mentioning that every once in awhile, you’ll come across a reason to use a double sharp (𝄪) or a double flat (𝄫). These are used purely as musical notation devices but become necessary when we discuss chord progressions in keys that use a lot of sharps or a lot of flats. Double flats and double sharps don’t create something new or special. Really it’s just one of the twelve notes with a different shirt on that it usually wears. You know the one shirt your Dad wears for special occasions in the summer...like that.

What are the Important Takeaway

To summarize what we’ve just gone through:

Western music is based on the twelve notes found in the Chromatic Scale.

A half step equals one fret increment.

We use the letters A-G, as well as accidentals like sharps (♯), flats (♭), or naturals (♮) to represent those twelve notes

Every once in a while, you’ll come across a reason to use a double sharp (𝄪) or a double flat (𝄫) but not often.