Intervals

An interval is a distance between two notes. This gets further refined into melodic intervals (two notes played one after another) and harmonic intervals (two notes played simultaneously).

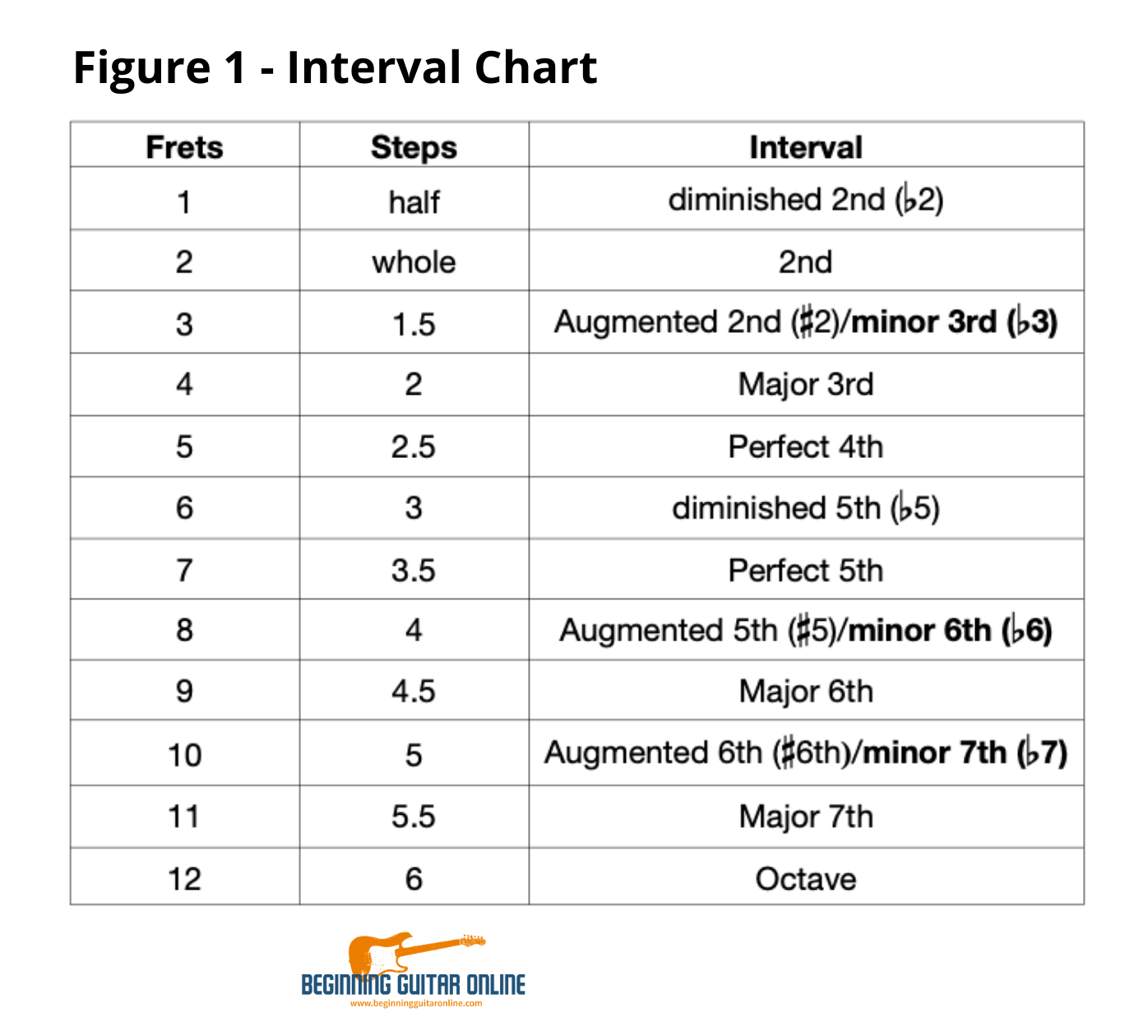

In our discussion of the chromatic scale, we covered that a half step between two notes represents moving up or down one fret on the guitar. The traditional name for this interval is a diminished second (♭2). If you were to move up by two frets, or a whole step, this is referred to as a second.

Figure 1 below is a table that shows the interval name and how many frets you would have to move between them. It also shows the number of steps between the notes that are associated with the interval.

Figure 2 above is the same one we used in our discussion of the chromatic scale and is brought back as a reference here. It’s important to remember that when we talk about intervals we are referencing a starting note (ex: C) and a target note (ex: D). Then we can analyze the distance between the two: a whole step, or two frets.

Because of these relationships between the notes we can use them to create patterns on the guitar that we can memorize. For example, a C to an E will always be an interval of a third and because of how the guitar is set up there are only a few ways to play them across the guitar. A few of them are depicted below in Figure 3.

One interval that you may be familiar with even without studying music is the octave. In its basic definition an octave is two pitches that are the same note (for example an A and an A) but one sounds higher or lower than the original pitch. On the guitar, an octave is spaced twelve frets apart, so the notes that are the open strings are the same at the twelfth fret, the notes on the third frets are the same at the 15th fret, etc.

The reason the two notes sound differently has to do with the physics of sound. Even though they have the same note name, the wavelength, or frequency (measured in Hertz (Hz)), that the pitches travel through the air is different. The frequency of a higher octave is always twice that of the lower pitch. Conversely, a lower pitch in an octave always travels through the air at half the speed of the highest pitch in the octave. This is why octaves sound differently even though the pitch names are the same.

So why throw science at you when you want to play guitar? If you want to eventually get into music production or recording the physics of sound becomes really important, and because it’s interesting!

For those of you who want to go super nerdy, intervals can be further categorized than what we’ve already discussed. For example:

Compound intervals are intervals that are higher than an octave

Past the octave, the notes repeat so what was the second scale degree becomes the ninth, the fourth becomes the 11th, etc.

Consonant intervals are thirds, fourths, fifths, and sixths

Dissonant intervals include seconds, sevenths, augmented, and diminished

Lastly, there’s an important characteristic of intervals to call out. When we discussed the intervals between C’s and E’s always being thirds, if we were to play these notes backward (E to C) we would not be playing a third. Instead, it would be a sixth. The same is true for other combinations of intervals as well: sevenths become seconds, fifths become fourths, augmented become diminished, etc. This is because, as we mentioned earlier, the interval is dependent on the relationship between the starting note and the target note.

To summarize what we’ve discussed:

Intervals represent the distance between two notes and can either be melodic intervals (one note played after the other) or harmonic intervals (both notes played together.

Specific intervals can be further grouped into consonant, dissonant, and compound intervals.

A whole step equals two fret increments